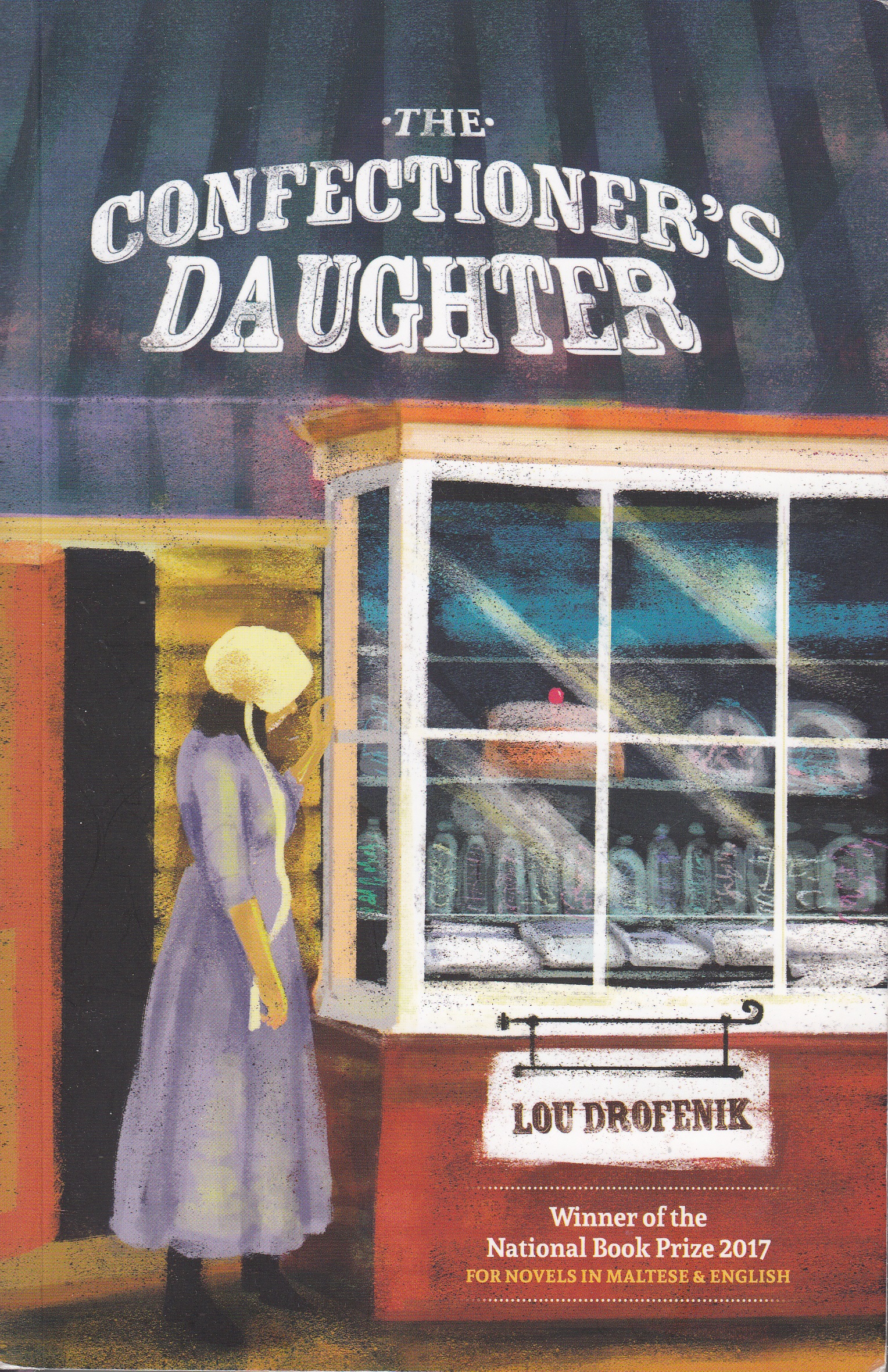

The motif of migration features in a number of your

novels, like Birds of Passage, The Confectioner’s Daughter and Echoes. It’s also something

you’ve personally experienced when, as a young woman, you left Malta to go to Australia.

What impact did this phenomenon have on you at the time, and later on as a

writer and an academic?

The motif of migration features in a number of your

novels, like Birds of Passage, The Confectioner’s Daughter and Echoes. It’s also something

you’ve personally experienced when, as a young woman, you left Malta to go to Australia.

What impact did this phenomenon have on you at the time, and later on as a

writer and an academic?

Migration changed my life completely, turned it

upside down, opened my eyes to many possibilities, freed me. I fell in love

with Australia when I arrived as a 21-year-old. I loved the wide landscape,

the gardens, the tree-lined avenues. It was an exciting time; thousands of

young people were arriving from all over Europe. I watched how different races

interacted with each other, worked together, accepted each other because they

were all in the same boat; starting from scratch, leaving old ways behind. In

the hostel where I lived, I met young women who were boarding there from country

Victoria. I was awed by their assertiveness, by the way they expressed

themselves, how they fought for their rights, how outspoken and uninhibited

they were. I wanted to be like them: confident and self-assured. Though I

didn’t know it then, that first year of settlement had a great impact on my

thinking and on my writing which came much later.

Women in your novels shine in their

ordinariness, which makes them extraordinary. Do you think this a fair

assessment? Why?

The women I write about are the women I knew. I

didn’t know any scholars. Most of the women — aunts, neighbours, shopkeepers — could barely write their own names, yet each one

of them had a story. The Birkirkara women I remember lived within the purview of their homes, going out to do the daily shop, hearing Mass, spending most

of their days cooking and washing — very ordinary lives you would say. And yet their simple existence contained a fascinating cornucopia of emotions, conflicts, taboos and superstitions. I have amassed a wealth of knowledge growing up in the midst of these incredible personalities.

Research is integral to your fiction

writing. How willing are you to bend the truth for the sake of the story?

History is factual. I do my very best to stay

within its boundaries. If I move away from historical facts, I declare it in the book. For example, in

Birds of Passage, I wrote about the Health Certificate for Prostitutes which, as

far as I know, did not exist; which is why I stated as much in the author’s notes.

Maybe I am wrong, but whenever I stayed in Gozo I

found that the people there were very spiritual. The women I met had a deep

love for their religion and an extraordinary faith, which jolted me

out of my cynicism. Whenever I stay in Gozo I have a feeling of goodness, of

benevolence, as if I am being looked after, cossetted and loved.

Maybe I am wrong, but whenever I stayed in Gozo I

found that the people there were very spiritual. The women I met had a deep

love for their religion and an extraordinary faith, which jolted me

out of my cynicism. Whenever I stay in Gozo I have a feeling of goodness, of

benevolence, as if I am being looked after, cossetted and loved.

Do you have an ideal reader in mind when

you’re writing a story? Does this condition your writing or style?

No. I write what I have to write, it comes and

there it is. I have to get the voices right to start writing otherwise there

is no story. I don’t have to see the characters but I must hear them. Once I

hear them then the story writes itself. Usually I know the ending first, and it

is very exciting to work out how the story will pan out to come to that ending.

To me there is no ideal reader. Every reader is a

unique person who invests time and money to read my work, who becomes involved

in what I wrote, and that is an honour a reader bestows on the writer. I have

great respect for each reader, and I am certain that a book is enriched each

time it is read, by what a reader brings to it from his or her experiences. Readers telling me that they fell in love

with my characters is the best gift they can give me.

Do you have any hobbies you’d like to

share with us?

We are self-sufficient here. We grow most of our

vegetables and fruit, lots of flowers and herbs to attract the bees, and we have

sheep to keep the grass down. I love gardening. My garden is where I exercise,

meditate, and where my characters speak to me.

What book, film or song would you

recommend to us?

What book, film or song would you

recommend to us?

To finish off: What’s the nicest thing

anyone has ever said to you?

My grown-up children ringing me and saying 'I

love you Mum' at the end of the conversation.

----------

If you want to read Lou Drofenik's books you can buy them from the links below:

If you want a FREE DIGITAL COPY of Lou's, BIRDS OF PASSAGE, click HERE for more details.

Comments

Post a Comment